My favorite painter is Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida. When I discovered his work at the IBM Gallery of Art and Science in New York City (1989, I think it was), I fell immediately in love with his paintings, with his style, with his world.

My favorite painter is Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida. When I discovered his work at the IBM Gallery of Art and Science in New York City (1989, I think it was), I fell immediately in love with his paintings, with his style, with his world. My favorite painter is Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida. When I discovered his work at the IBM Gallery of Art and Science in New York City (1989, I think it was), I fell immediately in love with his paintings, with his style, with his world.

My favorite painter is Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida. When I discovered his work at the IBM Gallery of Art and Science in New York City (1989, I think it was), I fell immediately in love with his paintings, with his style, with his world.

I recognize that Sorolla is not the greatest of painters. Vermeer, Raphael, and others had a deeper mastery of the art of painting than did Sorolla. Yet I prefer Sorolla. Why?

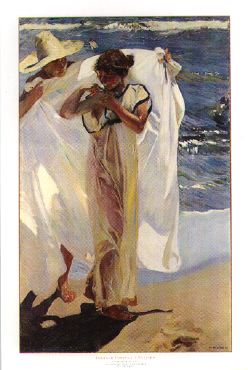

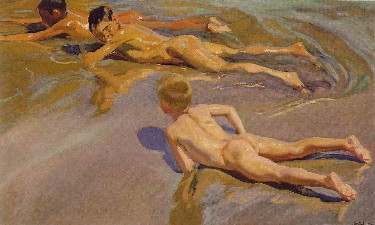

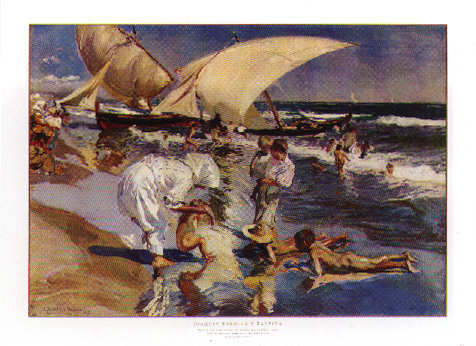

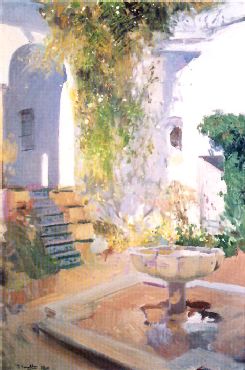

Partly it is his joyous style, with its focus on the play of light over the bright surfaces of things. Partly it is the subjects of his paintings, mainly the people and sun-drenched places of his native Valencia. Partly it is his imaginative and highly original use of color, which involves the juxtaposition of colors that one would think might clash but which come together to form a harmonious whole. Partly it is his depiction of sunlight on water, one of my favorite natural effects and one which no other painter I have seen has been able to capture in quite the way Sorolla did.

Who was Joaquín Sorolla? He was once a famous Spanish master, who took first Spain, then Europe, then America by storm. Unfortunately, much like his countryman and contemporary Enrique Granados, Sorolla lived and worked when the currents of modernism were roiling the art world around the turn of the 20th century. Early in his life Sorolla was seen as a realist radical, an innovator in plein air techniques who dared to paint ordinary people (even, as in Sad Inheritance, cripples); late in his life he was seen as a realist reactionary, stubbornly clinging to an outmoded style in the time of cubism, expressionism, and the triumph of modernism.

Sorolla's 1892 painting Otra Margarita (shown above) is an example of his early works, which portrayed scenes with social and sometimes religious themes. With Otra Margarita, Sorolla believed that he had achieved a realist style of painting that did justice to everyday life. The work, which won first prizes in Madrid and then at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago, evokes memories of Goethe's character Marguerite from Faust but presents at the same time a distinctively Spanish Margarita, a fallen woman in chains of Spanish society's making. Reportedly, the painting drove viewers to tears when it was presented at the Columbian Exhibition.

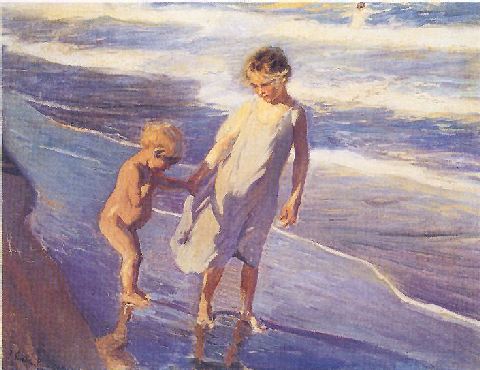

In 1900, several years after creating Otra Margarita and one year after painting the powerfully tragic Sad Inheritance, Sorolla consciously turned his back on art that evoked feelings of sorrow or pity and focused his prodigious energies on representing scenes of blinding light and vibrant color, mainly through paintings of the beaches and people of his native Valencia. From 1901 through 1905, he created 500 works that are consistent with his mature ideal of "natural painting". From these paintings came the body of work shown in a series of fantastically successful one-man shows in Paris, Berlin, London, New York, and Chicago (his 1909 show at the Hispanic Society in New York drew 160,000 visitors in the space of one month).

In 1900, several years after creating Otra Margarita and one year after painting the powerfully tragic Sad Inheritance, Sorolla consciously turned his back on art that evoked feelings of sorrow or pity and focused his prodigious energies on representing scenes of blinding light and vibrant color, mainly through paintings of the beaches and people of his native Valencia. From 1901 through 1905, he created 500 works that are consistent with his mature ideal of "natural painting". From these paintings came the body of work shown in a series of fantastically successful one-man shows in Paris, Berlin, London, New York, and Chicago (his 1909 show at the Hispanic Society in New York drew 160,000 visitors in the space of one month).

Following the success of Sorolla's shows in America, Archer Milton Huntington, the driving force behind the Hispanic Society of America, commissioned Sorolla to create a series of paintings representing the regions of Spain. This massive, multi-panel work, entitled Visions of Spain and still on view at the Museum of the Hispanic Society, took Sorolla seven years of grueling labor to complete (from 1912 to 1919) and sapped his strength. In 1920 he suffered a stroke, after which he painted very little. Sorolla died in 1923.

Sorolla has sometimes been labeled an impressionist, but that is not quite right. As the critic Henri Rochefort recognized on viewing Sorolla's Paris show in 1906, "this is not impressionism, but it is incredibly impressive". Sorolla's style is probably more accurately described as luminism — literally, the painting of light — or even, overcoming all collective categories, simply and uniquely Sorollism. He painted in the open air, often quite rapidly (as may have been necessary for an artist who created over 500 paintings in one four-year period). Some of his paintings appear almost unfinished, and he was not averse to leaving less-essential areas of the canvas in a rough state. Yet he could capture the finest details, and no painter before or since has been able to create such blinding fields and flashes of light as Sorolla in paintings such as Sewing the Sail and Return from Fishing (shown below).

In addition to his work as a painter of scenes of ordinary people at work and at play, Sorolla was much in demand as a portraitist. In this regard he was influenced by John Singer Sargent, whose "excellent naturalism" Sorolla much admired. Sorolla painted many gorgeous and touching portraits of his wife and daughters, as well as portraits of famous persons such as United States President William Howard Taft, Louis Comfort Tiffany (of Tiffany lamps fame), and King Alfonso XIII of Spain.

It is difficult to assess the extent of Sorolla's lasting impact. On the one hand, his work has been almost studiously ignored by twentieth-century critics (although there has been something of a small-scale Sorolla revival in recent years, as indicated by the New York show in 1989 and accompanying publication of Edmund Peel's book The Painter Joaquín Sorolla). Yet his work has continued to influence and fascinate a small number of painters, and the legacy of his paintings is starting to become better known. Perhaps he will yet receive the recognition he so richly deserves, when modernism is merely a bad memory and Sorolla's "natural painting" is understood as a unique way of capturing the light and color of joyous nature.

Here are some ways to explore the art and influence of Joaquín Sorolla:

Here are some ways to explore the art and influence of Joaquín Sorolla: